After more than 60 years of adventures at sea, first in the United States Coast Guard, then cruising the South Pacific in my own sailboat, kayaking in some of the world’s remote areas, followed in later life on 15 segments of world cruises, never had I experienced such ocean conditions as I did in late September.

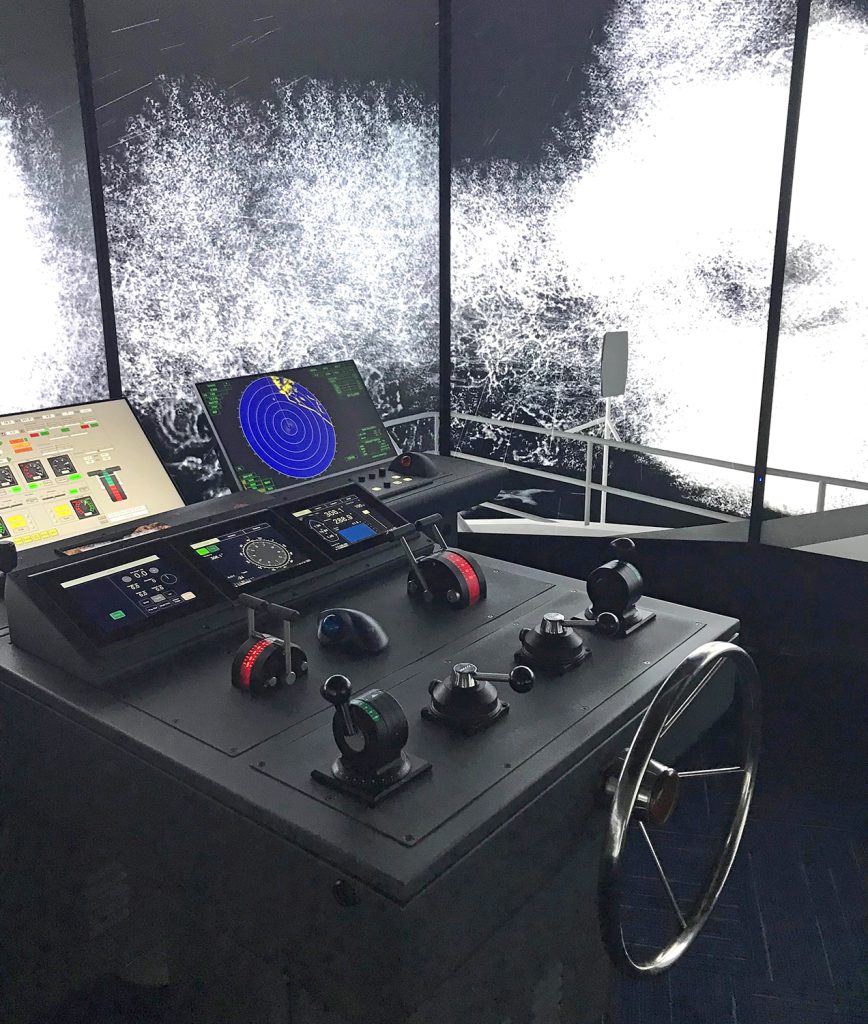

Endless, mountainous, confused swells piled one atop another, finally collapsing in an avalanche of black water and smothering foam.

Our bow plummeted into freak-wave troughs, burying itself in the onslaught of the marching waves, then lifting itself clumsily skyward as if struggling for a one last, life-saving breath.

Ferocious brine flooded across the deck, then slammed frighteningly into ship’s superstructure before soaring blindingly skyward into the sturdy panes of the wheelhouse high above.

Adding to the misery, horizontal storm blasts of icy sleet cut the visibility forward to near zero. Overall, this experience made the Winter waters of the Bering Sea, as seen on the reality TV series, “The Deadliest Catch,” seem lake-like.

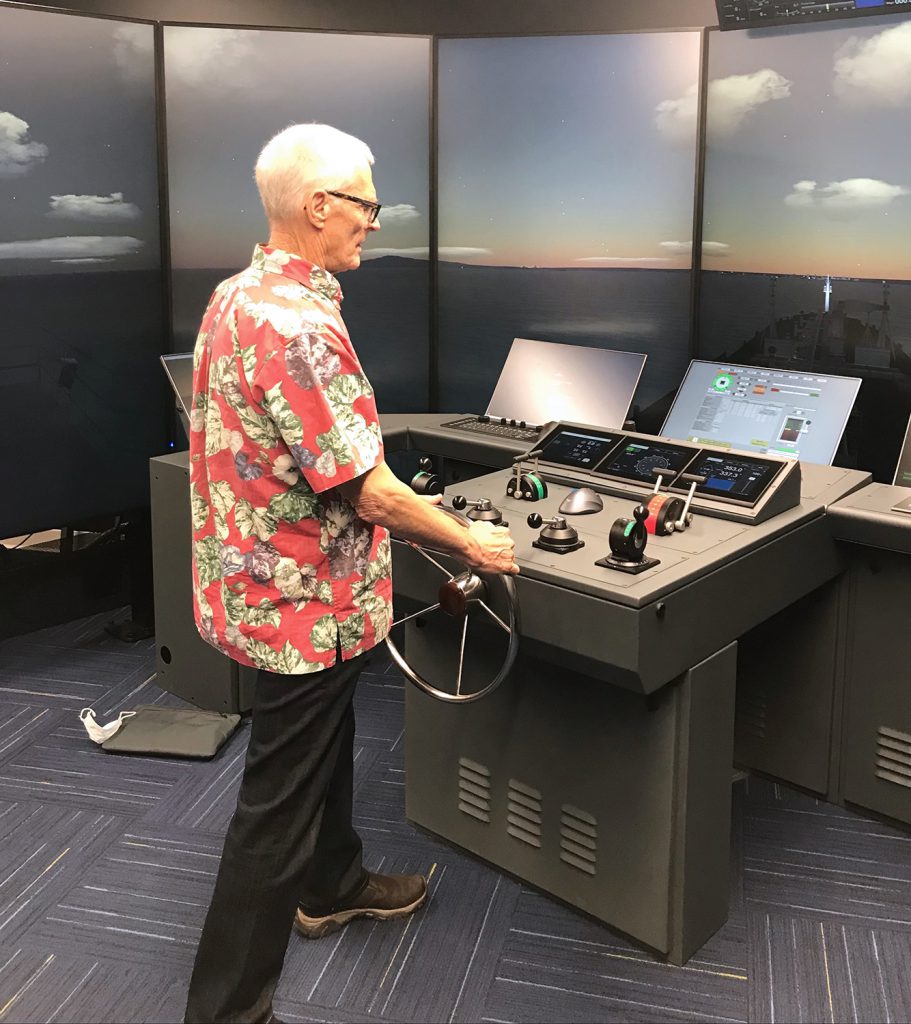

Despite the harrowing description, this heart-stopping, stomach churning voyage wasn’t as life-threatening as it sounds. It took place in the newly christened Full Mission Bridge Simulator at Orange Coast College’s new Professional Mariner Training Center on Coast Highway in Newport Beach, connected by the pedestrian span to the OCC Sailing and Rowing Base (adjacent to the Balboa Bay Club).

According to Maritime Lab Simulation Technician, 45-year-old John Vicente, “There isn’t a sea condition or type of ship that we can’t put into the simulator.”

In fact, the Full Mission Bridge Simulator is so sophisticated, the U.S. Navy is planning a visit in the near future to evaluate its use at some of their own training facilities, Vicente said.

The simulator comes as close to replicating a ship’s bridge as any in operation today globally, both in terms of physical appearance and instrumentation.

Programmed into the system currently are 45 different vessels, ranging in size from small fishing boats to high-speed ferries to mega-containerships.

To date, students can “captain” this fleet into 16 different geographic areas, including Los Angeles/Long Beach, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle and Singapore. To expand destinations or vessels, Vicente need merely plug in additional computer chips.

Adding to the simulator’s realism are giant video displays arrayed across 270 degrees, so student skippers can look beyond their instruments and information screens to ascertain visually what they’re navigating through and to – just like from the height of an authentic wheelhouse.

So realistic are the animated visuals that during several instructional sessions as Vicente shifted sea states from calm to near catastrophic, a couple of students had left on the run due to the onset of mal de mer (aka sea sickness).

And neophytes aren’t the only ones whose minds were fooled by the realness of the system. During early demos, two seasoned ships’ captains by habit either shifted the engines to neutral when they left the “bridge,” or braced themselves because of their ingrained sensations of rock-n-roll when the videos displayed storm scenes – even though the lab’s floors remained steady as a dock.

In fact, there isn’t an imaginable maritime scenario that can’t be programmed into the computer. Vicente can input ship traffic, threatening collisions, or career-ending groundings. In case of accidental groundings or collisions, the simulator will stop the simulation. Despite its 21st century sophistication, it will not contact insurance carriers.

With constant satellite updates, the system can even identify ships resting at assigned anchorages in Long Beach Harbor, or any of the 65 giant freighters currently backlogged at anchor from Long Beach/LA down to Huntington Beach, while awaiting docking instructions.

Choose an evening departure from Singapore, on any date, and the simulator will display the proper planets and stars at their correct amplitudes and azimuths, something a sextant navigator will appreciate.

Charted vessels will show up on the ship’s radar, as well as all the aids to navigation. Whatever was shown on the traditional printed charts will at the push of the correct button show up on one of the simulator’s monitors, replete with all updates and Notices to Mariners.

The system probably has “memorized” more information than any salty ol’ ship’s captain has amassed over decades of sea time.

“The capabilities are unlimited,” Vicente shared.

Even though the majority of the Center’s students grew up in the video game era, “students seem wowed by the technology,” Vicente opined. In fact, Vicente himself (an admitted bit of a nerd) is wowed by the technology, and every day is learning something new from the Russian designed-and-built, half-million-dollar system, one of just a handful currently in use in California, and the U.S.

Vicente’s marine background includes a decade in speed boats, followed by less gasoline-guzzling, gut-pounding ocean adventures in SeaDoos. However, his strength is simulators, having taught everyone from high school students to doctors in the use of “task trainers to full-body human patient simulators” at UCI’s School of Medicine.

Today, Vicente’s charted course is to help future mariners learn teamwork, navigation, helmsmanship, piloting skills and bridge management—and if necessary, how to tie a bowline.

For more information, visit https://occsailing.com.