By Nora Lehman | Special to the NB Indy

The Orange County Museum of Art is celebrating its 50th anniversary. Here is a look at how it all started.

“Do you know how to start?” actor, art collector and friend Sterling Hollaway asked Dorothe Curtis and Sue Green.

“Of course!” they answered. “We get on a plane and fly up and tell Mr. Graves we’re going to give him a show!”

The famously shy artist agreed, and that’s exactly what they did.

That was 1963.

If Holloway had any real concern at these ladies couldn’t mount an exhibition, all he had to do was reflect on the accomplishment of the previous two years.

In 1961, while there were well-organized aficionados supporting dance, theater and music programs locally, no group focusing on the visual arts had gotten under way. That was to be taken up by a group of community-minded women who had for a time been organizing and hanging artworks in City Hall.

The time had come to remedy that situation. In addition to Curtis, the initial meeting included Joan Brandt, Thelma Chastain, Judy Burndall, Gloria Irvine, Jane Lawson, Betty Mickle, Flo Stoddard, Dottie Ahmanson, Em Crary, Kay Farwell, Ailene Hays and Betty Winkler, the group’s first president.

It was Winkler who explained that their mission was “to bring to our community works of art of an established quality, a sound and viable program of art education,” she said, adding, “and find a suitable home.”

Volunteers all, calling themselves the Fine Arts Patrons of Newport Harbor, they and about 200 good friends who shared their enthusiasm got to work.

And work they did. In their first year, they:

- Obtained their corporate and not-for-profit status.

- Mounted a membership drive.

- Organized their first benefit party, in Rex and Joan Brandt’s garden.

- Launched their first art lecture series.

- Set up docent training classes.

- Started a scholarship fund for qualified high school and college art students.

- Organized bus trips to other museums, galleries and collectors’ homes.

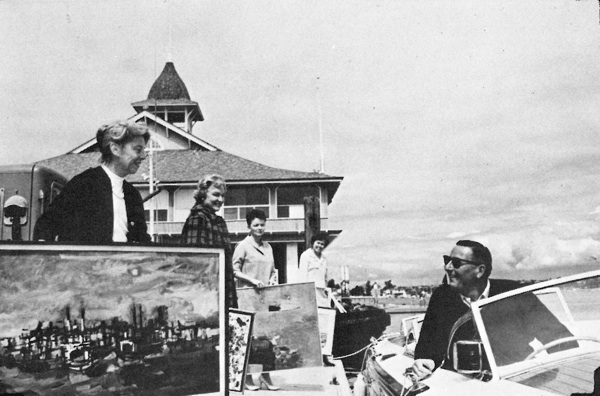

But, still lacking that “suitable home” – they were meeting at the Newport Harbor Yacht Club – the intrepid Winkler described how the Balboa Pavilion, which ahd been acquired by the Ducommon Realty Co. in that year, came to be the first location of the museum.

“I telephoned Mr. Ducommon at his Portuguese Bend home at 7 o’clock in the morning. I’m sure he couldn’t believe what he was hearing – some woman he didn’t even know was asking him if they could have the second floor of his building for their museum – for free!

“It was in pretty flaky condition,” she continued, “but when we agreed to make some improvements from time to time, he agreed to let us have it.”

The space was freezing in the winter and it was necessary to put heat in the rafters. Another renovation: installing louvres to cool it in the summer. And certainly not overlooked was the installation of restrooms.

Lighting? There was none. The electrical improvements were so sketchy at first that the night of the opening of their first exhibition, when the coffee pot was plugged in mid-party the whole building went dark. The fire department took a dim view of the number of extension cords strung around.

Nonetheless, the historic old building was theirs, and they now had a place for a shop, a sales and rental gallery and, most importantly, exhibition space.

Taking on the nitty-gritty of running a museum, many became master carpenters (tool belts and aprons became ubiquitous). They installed, plastered, spackled and painted the walls in preparation for each new show.

Such dedication moved one volunteer to announce that she had just hired a babysitter so she could come down and scrub floors.

Betty Steele became the registrar for the museum – an incredibly responsible position, involving inspecting each piece of incoming art and recording its arrival date, measurement, subject matter and condition – all in triplicate and always in white gloves.

They learned how to measure and plan exhibition space.

Betty Gold, who later opened her own gallery on La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles, designed and produced beautiful catalogues.

In addition they couldn’t ignore the more conventional, but necessary jobs of keeping membership files up to date, compiling invitation lists, addressing envelopes, stamping and mailing them, and keeping track of the replies.

They even became known for their superb cuisine at openings – 50 hors d’oeuvres? 500 hors d’oeuvres? No problem.

There were so many firsts in those years.

For instance, the basic planning behind them, they were ready to mount the first Pavilion show: “8 Figurative Painters from Los Angeles.” It was organized by Fred Wight, director f the UCLA Gallery and was followed by “Otis Art Awards.”

The next year – 1963 – Stephen Longstreet pulled together an exhibition of his own collection of Japanese prints, and then it was time for two of their own members, Curtis and Green, to put on the first Fine Arts Patrons’ show, “The Morris Graves Retrospective.”

The Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art didn’t come into existence until 1979, so these volunteer ladies were almost 18 years ahead of the modern art curve.

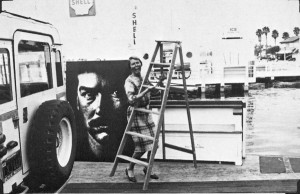

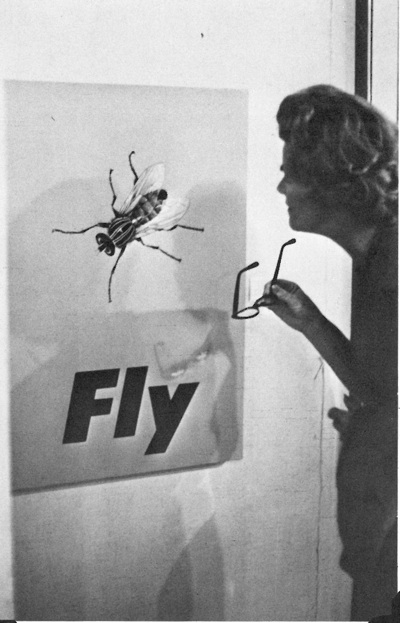

While putting on group shows featuring such favorite artists as Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, Georgia O’Keefe, George Luks and John Marin, they were also putting on amazingly avante garde exhibitions – especially for such a renowned conservative county – by artists such as hard-edged painter John Mclaughlin; abstract colorist Keneth Noland and the you rebel-artists who were just beginning to make names for themselves in Southern California: Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenberg, Wayne Thibaud, Llyn Foulkes, Joe Goode and Edward Ruscha, Paul Brach and Miriam Schapire, Rico Legrun, John Baldessari, Robert Rauschenberg and Richard Diebenkorn.

Sterling Holloway organized a show called “Especially for Children.” No adults were allowed in without a child in tow, and that exhibition, which went to the LA County Museum of Art, was their first traveling show.

“We Shall Overcome” could have been the 1964 theme song. When the first Collectors’ Show showed signs of running out of wall space, it was apparent that more gallery space would be needed. It was found on John Wayne’s yacht, the Wild Goose.

That same year, the University of California regents were coming to the county for the dedication of UC Irvine. University officials had planned an exhibition of their 1963-64 artists, but had no gallery space. The Fine Arts Patrons offered the Pavilion. Dorothy Ahmanson was the party planner for the event, and it turned out to be a pretty elegant affair.

President Johnson was to come out for the dedication and university officials asked the Fine Arts Patrons to invite him to a lunch.

They did, only to find that the Pavilion room had already been booked for a wedding reception. The Fine Arts Patrons lined up a new venue and paid for, addressed, stamped and mailed new invitations for the reception.

And the president didn’t show!

Fundraisers were necessary, of course, so Le Bon Marche – a very elegant jumble sale – was inaugurated. That was followed by the Beaux Arts Ball and, held in 1971 in the Pavilion, the Art Auction.

All over he world, 1968 was a year of great change. So too for the Fine Arts Patrons, which became the Newport Harbor Art Museum. A paid director, Tom Garver, came on board. And the first co-ed board of directors was elected, with Ailene Hays’ husband, Jerry, taking the gavel from two-time chair Patsy Gibson.

Gibson moved over to chair the new Museum Council fundraising group. She and he husband, Walter, sometimes paid the staff when funds ran low.

“New Painting in Los Angeles” was the last exhibition in the Pavilion, in 1971, 10 years after the Patrons’ founding.

In summing up those ten years in the catalogue “The Audacious Years,” Sterling Holloway had the final word:

“To the Ladies, You’ve come a long way, baby!”

Awesome!!!!!! to cool. Ladies do it right!

diane stovall